I was a Native/American Indian (Tarahumara, adopted Lakota) born and raised in a farmhouse just on the outskirts a Nebraskan small town of 10k people. For 25 years, I experienced the blessing of so many things I never thought I would feel the absence of so painfully that it caused a ten year-long identity crisis and dark struggle with my mental health after I moved straight to the city of Los Angeles, CA.

What I felt everyday back home was connection to the land because it was wide open spaces wherever you were. I experienced a community that was so close in proximity and small in size that it felt like a large tribe in the traditional spirit of that concept. I felt a sense of small community that wasn’t so over-burned with itself in size or by its colonial systems that I never felt lost in it.

I was always aware of my indigenousness and tussled with what that meant: how “Native” I was and if how you grew up determined your legitimacy in any way. In fact, it wasn’t until I moved to Los Angeles that I truly, fully and proudly embraced my identity as Native and Indigenous… as an act of rebellion against how anti-Indigenous this city was—it was a grand manifesto of how badly “run-away colonialism” had become. I dawned feathers in my head-band daily, I mixed in Indigenous words into my vocabulary when I spoke, I made most things about my identity an embodiment of how this “little Indian in a big city” had a lot to say about the colonizer’s structurally rotten, socially decayed and morally void way of life he claimed to be “superior” for over 500 years.

This symbolic turning away from everything I resented and hated about the colonizer’s world ended up hurting me much worse because of the cultural and societal alienation, especially from those who didn’t understand where I was coming from. The challenges were daily… hourly, the racist comments on the street, being told to “get over what happened” to my people or processing the craziest remarks “I thought all of your people died off. I never met a real Indian before.”

I delved so deeply into my community as a result. I volunteered at and went to every powwow. Soon I became an ambassador for the Red Circle Project at APLA (Aids Project Los Angeles). I helped run the Through my Eyes Indigenous film festival. I worked on a number of projects with a number of up-and-coming Native filmmakers. I volunteered with Indigenous Pride, an LGBTQ and Two Spirit organization. Most relevantly, I was also admitted to United American Indian Involvement in their Seven Generations program hoping it would help me with my mental health crisis in a culturally competent way spending years in that program. I would eventually end up at Standing Rock for several months organizing our internationally-known protest camp against the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline, knowing where I had just come from—feeling like I had reached the epitome of what “Indigenous Resistance” against colonizer violence meant today.

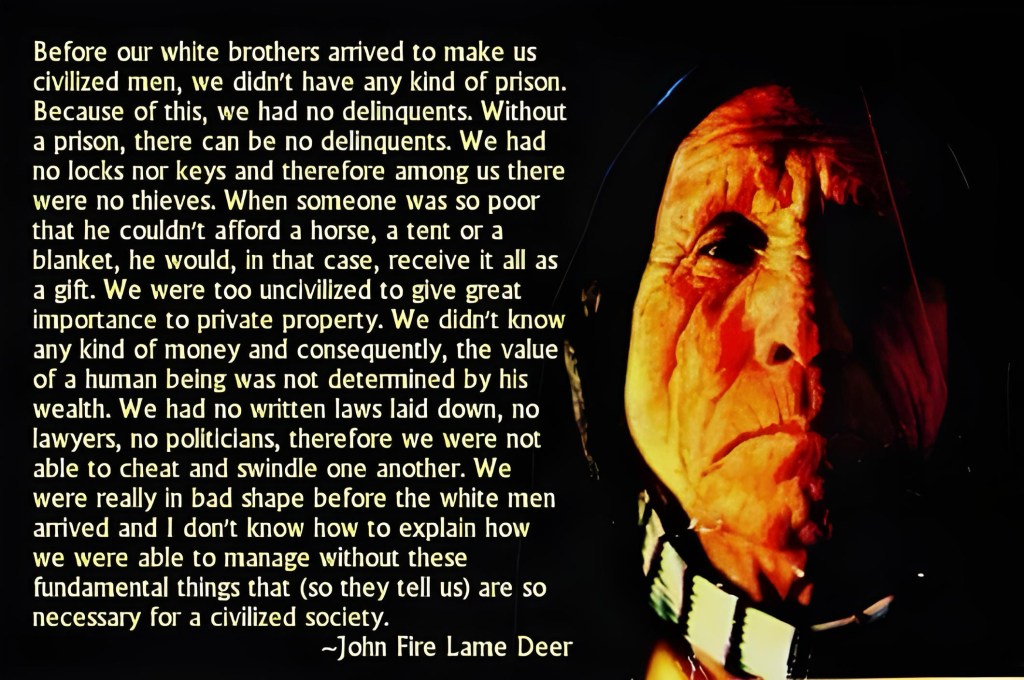

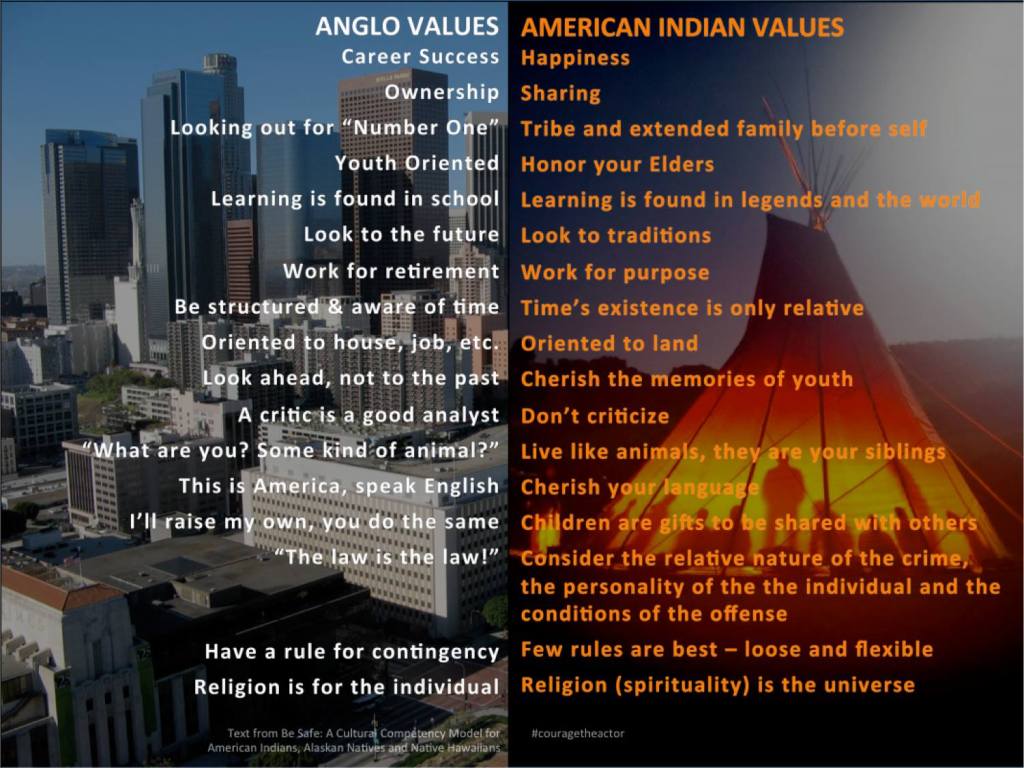

I spent so much time lost, inspired, enraged and broken in a million pieces for the first seven years I spent in Los Angeles; having engaged in a “spiritual battle” against the massive monster that was “colonialism” and how LA represented the monster I had to slay in the name of the once vast and open land that had been taken from my once free-people. Even if it meant simply vanquishing it by calling it by its name and using my educated background to call out every aspect of its inherent rot and corrupt nature. This would also include advocating for ideas that most people today would struggle to see from my cultural point of view: “There was no such thing as “the homeless” in my peoples’ time.” or “When my people spoke to each other in our time, we didn’t intentionally choose to “lie” to each other by using cold “procedural speak” and “company script” that was void of humanity, compassion the intention of listening.” to statements like “If my ancestors saw that we lived in a time where there was always thick mile of concrete underneath our feet and chose to live in boxes inside of boxes separated from each other, they would call us sick and lonely.”

…My way of thinking has been considered new, revelatory as well as both foolish and unprofitable by both some non-Indigenous and Indigenous people alike. But I continue to improve my voice and my cultural platform to point out so many truths about the poisonous colonizer’s world and how it greatly affects our mental health, stunts our spiritual growth as one human race and further prioritizes things that only encourage the very obsessions my people have always fought against: greed, short-sidedness, disrespect and imbalance.

Today, after ten years, I live a good and comfortable life, now settled in the outskirts of Los Angeles by the forest. I continue my fight so I can define my cultural viewpoint and someday… “defeat” the monster that is “the colonizers dystopia” and how it not only is anti-Indigenous in a multitude of ways but its very nature is self-destructive and self-defeating.

I very much engage in the colonizer’s world as a “professional” and have become very good at it, but every day I further work to shape and build the hill I will die on, which is fighting for a true revelatory realization of what it means to be Indigenous. Unsurprisingly, it’s not “spirit animals, dream catchers, hippie subculture or even simply “environmentalism.” It’s something much deeper that calls us to continually reflect and challenge the society we’re building around us and how it’s over-complex, greed and fear-based nature could potentially cause its downfall but surely and evidently lead to so much human suffering.

Written by: Courage

If interested, watch a video of me being interviewed about this subject back in 2016:

Courtesy of The Trystan Foundation